CONTENTS

In Fukushima, the fishing industry challenges everyone involved to stick to safety standards even higher than Japan requires. Find out why Joban-mono isn’t just tasty, it’s also well-tested for safety.

Getting the Fishing Industry Back on Its Feet at the Shiome Sea

The Tohoku Earthquake that occurred on March 11, 2011, and the following nuclear meltdown, was a shock to people around the world. Even today many people's hearts are deeply scarred by the destruction, and the nuclear disaster damaged Fukushima's farms, fisheries, and all of the prefecture's food industries. No matter how famous the branding of "Joban-mono fish" might have been before that date, no Fukushima brand could be popular enough to avoid the far-reaching effects of this terrible disaster.

However, the Japankuru team has recently been writing about the current status of Fukushima's fishing industry and the way it is being rebuilt, focusing in on fisheries in the cities of Iwaki and Soma in parts three and four of our Joban-mono series. We spoke to Iwaki Fisheries Cooperative Association Vice-President Mitsunori Suzuki and Soma Futaba Fisheries Cooperative Association President Kanji Tachiya, who each explained their sincere confidence in Joban-mono, while gazing out onto the water of the "shiome" (潮目, ocean current junction). When it comes to the ocean off the coast of their own home towns, they spoke with conviction, unshakeable even in the shadow of the 2011 disaster.

The shiome off the Joban coast (stretching along Fukushima's shores down to Ibaraki) is the spot where the cold Oyashio ocean current and the warm Kuroshio current meet, and this expanse of water is sometimes called the Shiome Sea (or "Shiome no Umi," 潮目の海). It's not just a place where fish hailing from both ocean currents can be caught―this meeting point results in lush plankton growth, and this ample food source for the fish makes the area an especially good fishing ground. The fish caught off the Joban coast―plump, oily, and full of flavor―have long been the pride of Fukushima's fishermen. Nobody could have expected such a dramatic change to the local fisheries' fortunes. Not only did the earthquake and tsunami steal away people's homes, their friends, and their family, but the radiation remaining in the area after the nuclear disaster has dogged the Joban-mono fishing industry with rumors, kicking the people of Fukushima while they were down. Even so, the fishery workers are determined to get back on their feet, and have established new policies together with Fukushima's prefectural government, in order to win back consumer confidence. Since these initiatives started taking shape, they've established new testing operations, and have been working slowly but surely to re-establish the local fishing industry.

What Are “Testing Operations”?

Fukushima's coastal fishing and offshore trawling industries had no choice but to halt operations after the nuclear disaster. Close to ten years since the disaster, however, over 60,000 monitoring tests have been performed on the local marine life, checking radiation levels. Many varieties of fish and other seafood caught nearby have been confirmed as safe for consumption, easily clearing the national safety standards set by the Japanese government. In turn, restrictions have been relaxed little by little, permitting the local fishing industry and seafood sellers to return to work on a small scale (restricted only to species that have surpassed safety standards), as a watchful eye is kept on the market's reactions all the while. This process, and the careful monitoring policies, are Fukushima's "Testing Operations." According to data released by the Fukushima prefectural office this year (on March 26, 2020), 231 species of fish and seafood have already been confirmed safe.

The term "monitoring tests" refers to the radiation testing done according to national Japanese standards, meaning that there is no problem with shipping any fish or seafood that meets those standards to market. However, Iwaki, Soma, and the fisheries of Fukushima Prefecture perform their own additional radiation testing every day, on top of the monitoring tests, to give consumers an extra level of assurance when it comes to safety―and the fisheries hold their fish and seafood to even higher safety standards than the Japanese government. These additional fishery tests are called "screening tests," and the people of Fukushima's fisheries want you to understand that these days, no Joban-mono makes it to market unless it has been proven safe through these two testing processes!

Monitoring to Guarantee Safety

The Fukushima Agricultural Technology Center plays an important role in ensuring the safety of Fukushima's agriculture, forestry, and fishing industries, by performing monitoring radiation tests on the prefecture's agricultural and marine products. You might call this place the key to revitalizing those industries in Fukushima, and wiping away the damaged reputation. Joban-mono fish is one of the many local products tested here, and the final judgments―deciding which kinds of fish are safe to catch, and which should still be left alone for now―are made based on the center's results.

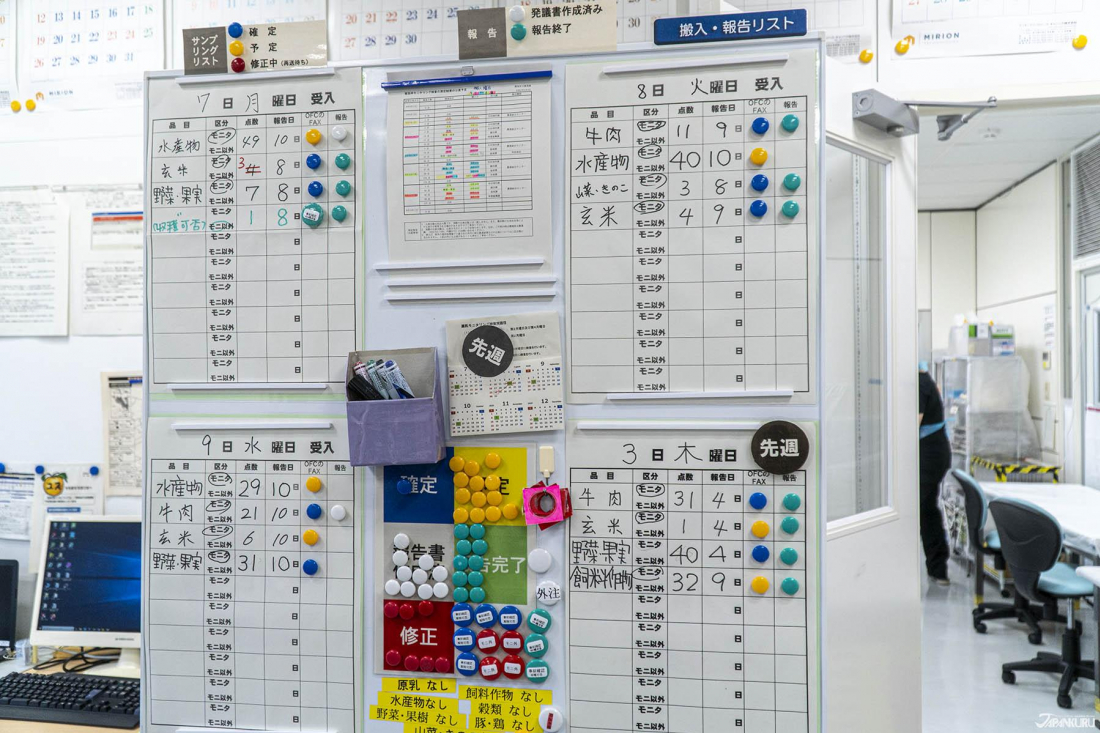

The Fukushima Agricultural Technology Center's research is done in the city of Koriyama, where they perform monitoring tests on Fukushima's agricultural and marine products on a set cycle, testing vegetables, fruit, seafood products, edible wild plants, mushrooms, honey, grains, dairy products, meat products, eggs, and feed crops. There are always so many items waiting to be tested, sometimes the center even outsources the testing of a portion of the products, like processed foods and fodder, to other labs with testing equipment. In addition to directly publishing their test results for experts, the monitoring results are added to an official Fukushima prefectural website, so anyone can check the data at any time.

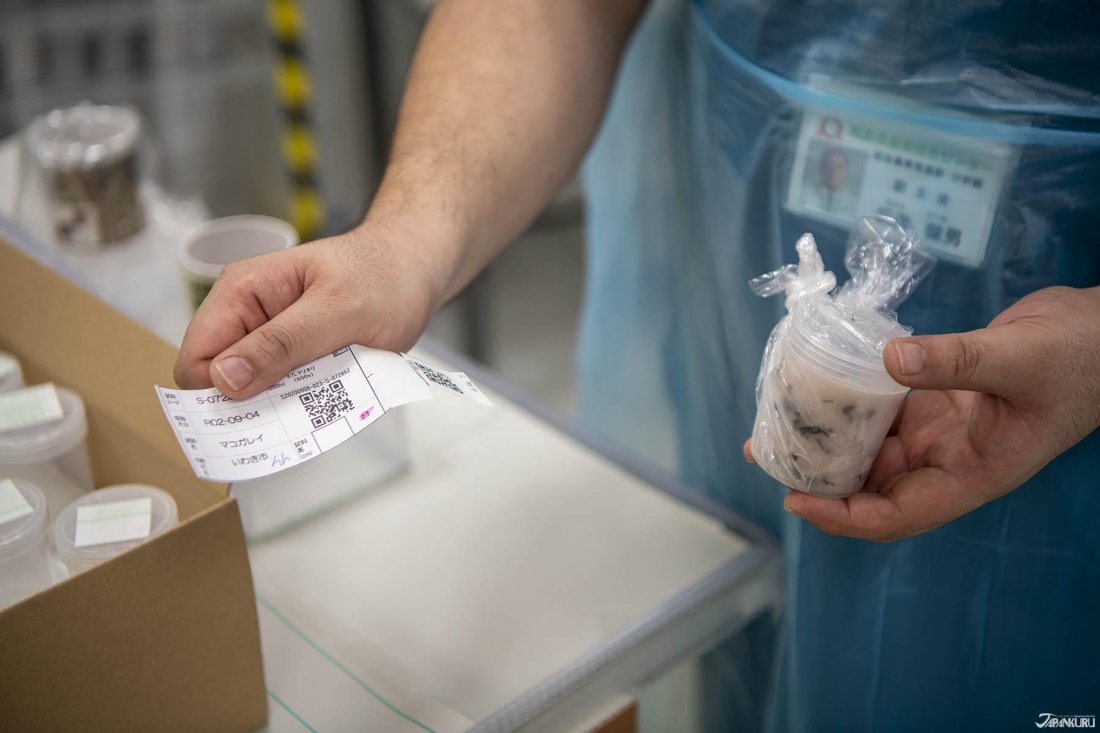

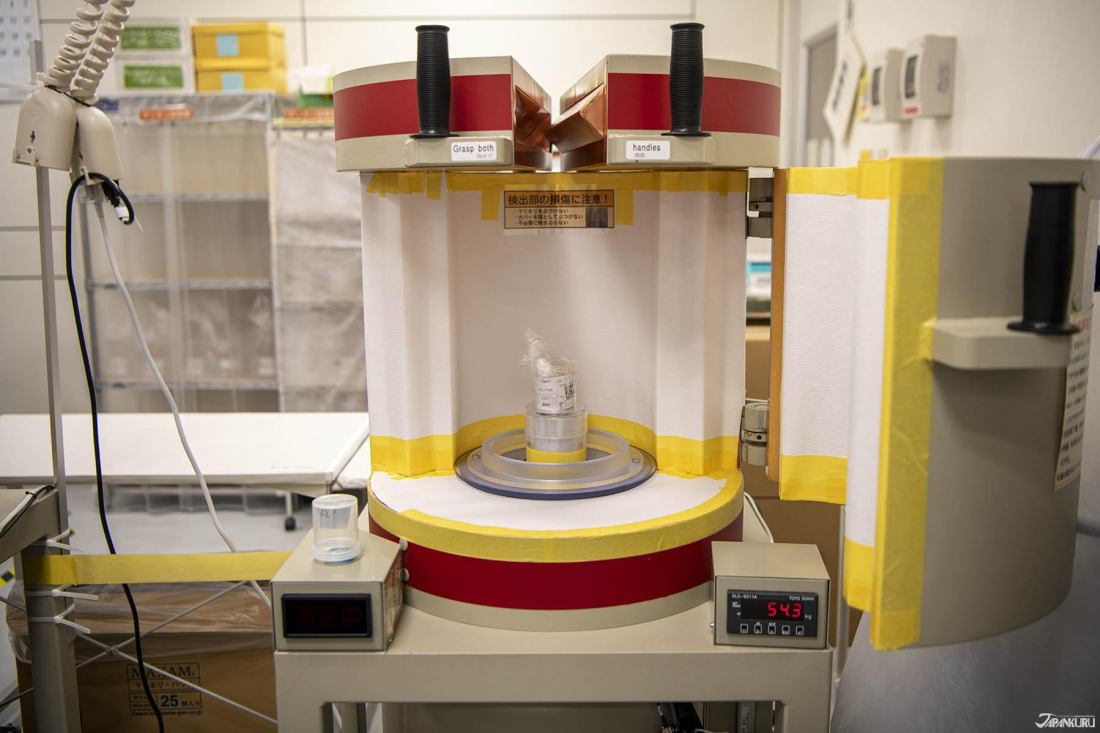

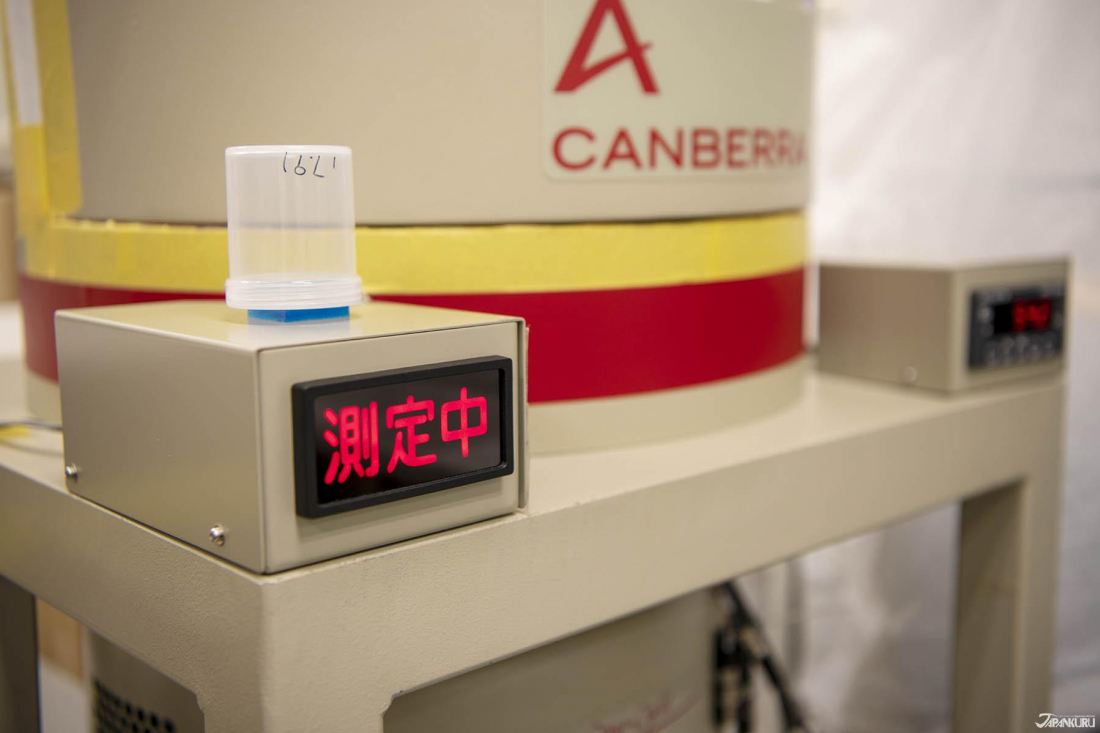

Visiting the center, the Japankuru team was able to see exactly what kind of testing is done on Joban-mono, and observe the monitoring process as it was being performed. Before even entering the labs, all staff members undergo a quick radiation check with a special detection wand, since even the smallest amounts of radioactive material (stuck in a person's clothes or hair) could affect their test results. Similarly, when agricultural or marine products are mailed to the center for testing, all the packaging material has to be checked to make sure it's not contaminated with any stray radioactive material either. When a product arrives at the Agricultural Technology Center for testing, it's carefully removed from its wrapping, cut up into pieces as fine as possible, stuffed into specially-made containers, weighed, and then finally placed into an extremely accurate germanium-based semiconductor detector, to have its radiation levels measured. The researchers analyze the machine's results, and then publish those results to the public.

At this time, the Fukushima Agricultural Technology Center lab has eleven germanium-based semiconductor detectors for testing radiation levels, and nine researchers working together. The machines are periodically inspected by the International Atomic Energy Agency, to maintain the accuracy of each test. In 2017, the lab introduced a new QR code system, which registers all of the information collected throughout the testing process. Thanks to these measures, the laboratory's radiation testing efficiency has risen, and they now average about 150 tests every day.

According to Hitoshi Kusano, head researcher at the Fukushima Agricultural Technology Center, the vast majority of the agricultural and marine products tested in recent years have been within the accepted radiation safety standards. The official national safety standard for marine products is under 100 becquerels of radiation per kilogram (100Bq/kg), and apparently, none of the marine fish samples have gone over that limit since March of 2015. Anybody can take a tour of the monitoring labs at the Fukushima Agricultural Technology Center, and have the testing process explained in detail by the experts, to see these results for themselves. (Just make an appointment ahead of time!)

Screening for Peace of Mind

The Fukushima Agricultural Technology Center is a government agency and the monitoring tests stem from Japan's food sanitation laws, but the Fukushima Federation of Fisheries Cooperative Associations (which organizes Fukushima's fishing industry) has its own approach to ensuring the safety of marine products and reassuring consumers. In the fish markets of Iwaki and Soma, the federation tests their own samples of marine life, in the system they call screening. Every day, the screening process collects a sample from every single species of fish and seafood caught that morning, and tests them all for safety.

Japan's food safety laws set the safety standards for radioactive cesium in food products at 100Bq/kg or less, but Fukushima's fisheries keep much stricter standards to give consumers extra peace of mind. The fisheries only allow a maximum of 50Bq/kg in their fish and seafood. That means that no Fukushima marine products make it to market unless they test in at under 50Bq/kg, significantly less radiation than the Japanese government safety limits.

Even more interestingly, if you compare Japan's national standard of 100Bq/kg to other countries' food safety laws, you'll see that it's actually already stricter than many other parts of the world. For example, the safety limit of the Codex Alimentarius (a collection of internationally recognized standards set by the UN and WHO) is 1000Bq/kg, the United States' standard is 1200Bq/kg, and the EU allows up to 1250Bq/kg. Looking at the hard data, it's clear that Fukushima's fishery workers are aiming for some extremely strict standards, and very safe products.

Iwaki's Onahama Fish Market and Soma's Haragama Fish Market each have their own testing rooms, where they carry out their daily sampling activities, and test each kind of fish caught that day. These testing rooms don't have quite as many testing machines as the Agricultural Technology Center lab, but in order to increase both speed and accuracy, the facilities periodically buy new machines and repair aging ones. Onahama Fish Market has nine machines right now, but they're not all the same―the oldest ones take about 40 minutes to fully process a sample, and the newer ones can do the same work in just five!

In the case that a sample does go over the strict limit of 50Bq/kg, sales are immediately halted on all fish of the same species, and the sample is sent to the Fisheries and Marine Science Research Center for more precise and in-depth testing. If the secondary testing proves that the sample really did go over 50Bq/kg, then that species of fish is entirely recalled, and fishing boats are temporarily prohibited from catching that variety. In actual practice, a sample of flounder caught in Iwaki back in July 2018 was found to contain 59Bq/kg of radioactive cesium. Of course, this is well within the safety limits set by the Japanese government, but since it went over the 50Bq/kg limit set by the fisheries themselves, flounder sales were stopped. For a month following the incident, local flounder were continuously sampled and tested via the monitoring process, and flounder fishing only resumed once the samples again fell under 50Bq/kg.

The fact that local fishery workers can have such confidence in the fish they catch is surely thanks to those strict standards, and as the screening continues each and every day, it's clear that the people of Fukushima's fisheries are working hard to make sure consumers don't lose faith in Joban-mono again. Looking around Japan, you won't find another prefecture with a testing system like this, and the hard data speaks for itself. "No matter how much data you put in front of them, 10% of people just won't accept it," said Maeda of the Onahama Trawler Fisheries Cooperative Association, "but we face the 90% of people who are willing to hear what we're saying, and every day, we try our best to communicate our mission while we continue our strict testing." He finished his comment by mentioning that, in fact, almost none of the samples tested in the last year registered as having detectable radiation at all.

Telling the Difference Between Monitoring and Screening

Reading this far, can you see how Fukushima Prefecture's "monitoring" and the fisheries' "screening" vary? Let's sum up the differences for reference.

In Fukushima Prefecture, there are two radiation testing structures: monitoring testing performed by the prefectural government, and screening testing done on samples from each day's catch, performed by the fishery organizations.

[Similarities]

Both processes measure the radiation in marine life, and judge the safety of the marine products based on analysis of this scientific data. This basic testing process is essentially the same for both monitoring and screening.

[Differences]

●Organizations

Monitoring: Run by Fukushima Prefecture, based on Japan's governmental standards.

Screening: Run by independent, non-governmental fisheries associations.

●Standards

Monitoring: National safety standards (100 Bq/kg), established with residents of all ages in mind.

Screening: Stricter standards (50Bq/kg), established to give consumers additional peace of mind.

●Facilities

Monitoring: Fukushima Agricultural Technology Center

Screening: Fukushima Federation of Fisheries Cooperative Associations (Onahama Fish Market/Soma Haragama Fish Market)

●Frequency

Monitoring: Twice a week.

Screening: Every fishery business day.

Joban-mono – A Part of Everyday Life?

After many long years, and thanks to the hard work and cooperation of the government and Fukushima's fishery workers, Fukushima's marine products are finally finding their way back into the lives (and diets) of local residents. Government agencies and fishery associations share their official testing results, research centers like the Fukushima Research Institute of Fisheries Resources invite local students, community organizations, and average citizens to attend seminars, and accurate information about radiation is finally reaching the public. The many efforts are winning back the people's confidence in Joban-mono.

In 2017, the City of Iwaki Department of Agriculture, Forestry, and Marine Products set up the website "Joban-mono," introducing information on the region and the local fish, popular recipes, cooking tips, and all sorts of Joban-mono tidbits. In addition, these days on the 7th of every month, Iwaki celebrates "Fish Day" (魚の日), promoted in cooperation with local fish markets, restaurants, bars, and gift shops. When the Japankuru team visited Iwaki, we stopped in at Shuen-teru, a cozy bar and restaurant, and found that it too was a part of the promotion―two adorable little banners stood on the shelf, proclaiming "Joban-mono" and "Fish Day."

If we're talking about famous spots that sell Joban-mono, fish market Ookawa Uten in Iwaki is a clear choice. Not only is it popular with locals, but it's been around since the Meiji era (1868-1912). The shop sells fresh-caught fish and seafood, plus some prepared dishes, like "uni no kaiyaki" (ウニの貝焼き, sea urchin cooked in a clamshell) and "katsuo no warayaki" (カツオの藁焼き, skipjack tuna grilled over straw). These dishes are regional specialties, and for special events and festivals, staff put on grilling demonstrations in front of the shop, for locals to enjoy.

On this trip, we saw people buying, cooking, and eating all kinds of local seafood as we wound our way through fish markets large and small, hotels, restaurants, and all throughout Iwaki and Soma. As far as the Japankuru team can tell, Joban-mono has once again found a place in the everyday life of locals in Fukushima. It's clear that this is thanks to the hard work of Fukushima's fishery workers, and Fukushima Prefecture, over the course of almost ten years.

This time, we focused on the testing systems used to check radiation levels in Fukushima's marine products. Next time, we'll be looking more at the Fukushima Research Institute of Fisheries Resources, and the research they conduct on Fukushima's ocean waters and marine life. Keep an eye out for more in-depth information, and a look inside the premises of another fascinating facility.

For more info and updates from Japan, don't forget to follow Japankuru on twitter, instagram, and facebook!

Details

NAME:Fukushima Agricultural Technology Center (農業総合センター)

COMMENT

FEATURED MEDIA

VIEW MORE

A New Tokyo Animal Destination: Relax & Learn About the World’s Animals in Japan

#pr #japankuru #anitouch #anitouchtokyodome #capybara #capybaracafe #animalcafe #tokyotrip #japantrip #카피바라 #애니터치 #아이와가볼만한곳 #도쿄여행 #가족여행 #東京旅遊 #東京親子景點 #日本動物互動體驗 #水豚泡澡 #東京巨蛋城 #เที่ยวญี่ปุ่น2025 #ที่เที่ยวครอบครัว #สวนสัตว์ในร่ม #TokyoDomeCity #anitouchtokyodome

Shohei Ohtani Collab Developed Products & Other Japanese Drugstore Recommendations From Kowa

#pr #japankuru

#kowa #syncronkowa #japanshopping #preworkout #postworkout #tokyoshopping #japantrip #일본쇼핑 #일본이온음료 #오타니 #오타니쇼헤이 #코와 #興和 #日本必買 #日本旅遊 #運動補充能量 #運動飲品 #ช้อปปิ้งญี่ปุ่น #เครื่องดื่มออกกำลังกาย #นักกีฬา #ผลิตภัณฑ์ญี่ปุ่น #อาหารเสริมญี่ปุ่น

도쿄 근교 당일치기 여행 추천! 작은 에도라 불리는 ‘가와고에’

세이부 ‘가와고에 패스(디지털)’ 하나면 편리하게 이동 + 가성비까지 완벽하게! 필름카메라 감성 가득한 레트로 거리 길거리 먹방부터 귀여움 끝판왕 핫플&포토 스폿까지 총집합!

Looking for day trips from Tokyo? Try Kawagoe, AKA Little Edo!

Use the SEIBU KAWAGOE PASS (Digital) for easy, affordable transportation!

Check out the historic streets of Kawagoe for some great street food and plenty of picturesque retro photo ops.

#pr #japankuru #도쿄근교여행 #가와고에 #가와고에패스 #세이부패스 #기모노체험 #가와고에여행 #도쿄여행코스 #도쿄근교당일치기 #세이부가와고에패스

#tokyotrip #kawagoe #tokyodaytrip #seibukawagoepass #kimono #japantrip

Hirakata Park, Osaka: Enjoy the Classic Japanese Theme Park Experience!

#pr #japankuru #hirakatapark #amusementpark #japantrip #osakatrip #familytrip #rollercoaster #retrôvibes #枚方公園 #大阪旅遊 #關西私房景點 #日本親子旅行 #日本遊樂園 #木造雲霄飛車 #히라카타파크 #สวนสนุกฮิราคาตะพาร์ค

🍵Love Matcha? Upgrade Your Matcha Experience With Tsujiri!

・160년 전통 일본 말차 브랜드 츠지리에서 말차 덕후들이 픽한 인기템만 골라봤어요

・抹茶控的天堂!甜點、餅乾、飲品一次滿足,連伴手禮都幫你列好清單了

・ส่องมัทฉะสุดฮิต พร้อมพาเที่ยวร้านดังในอุจิ เกียวโต

#pr #japankuru #matcha #matchalover #uji #kyoto #japantrip #ujimatcha #matchalatte #matchasweets #tsujiri #말차 #말차덕후 #츠지리 #교토여행 #말차라떼 #辻利抹茶 #抹茶控 #日本抹茶 #宇治 #宇治抹茶 #日本伴手禮 #抹茶拿鐵 #抹茶甜點 #มัทฉะ #ของฝากญี่ปุ่น #ชาเขียวญี่ปุ่น #ซึจิริ #เกียวโต

・What Is Nenaito? And How Does This Sleep Care Supplement Work?

・你的睡眠保健品——認識「睡眠茶氨酸錠」

・수면 케어 서플리먼트 ‘네나이토’란?

・ผลิตภัณฑ์เสริมอาหารดูแลการนอน “Nenaito(ネナイト)” คืออะไร?

#pr #japankuru #sleepcare #japanshopping #nenaito #sleepsupplement #asahi #睡眠茶氨酸錠 #睡眠保健 #朝日 #l茶胺酸 #日本藥妝 #日本必買 #일본쇼핑 #수면 #건강하자 #네나이토 #일본영양제 #อาหารเสริมญี่ปุ่น #ช้อปปิ้งญี่ปุ่น #ร้านขายยาญี่ปุ่น #ดูแลตัวเองก่อนนอน #อาซาฮิ

Japanese Drugstore Must-Buys! Essential Items from Hisamitsu® Pharmaceutical

#PR #japankuru #hisamitsu #salonpas #feitas #hisamitsupharmaceutical #japanshopping #tokyoshopping #traveltips #japanhaul #japantrip #japantravel

Whether you grew up with Dragon Ball or you just fell in love with Dragon Ball DAIMA, you'll like the newest JINS collab. Shop this limited-edition Dragon Ball accessory collection to find some of the best Dragon Ball merchandise in Japan!

>> Find out more at Japankuru.com! (link in bio)

#japankuru #dragonball #dragonballdaima #animecollab #japanshopping #jins #japaneseglasses #japantravel #animemerch #pr

This month, Japankuru teamed up with @official_korekoko to invite three influencers (originally from Thailand, China, and Taiwan) on a trip to Yokohama. Check out the article (in Chinese) on Japankuru.com for all of their travel tips and photography hints - and look forward to more cool collaborations coming soon!

【橫濱夜散策 x 教你怎麼拍出網美照 📸✨】

每次來日本玩,是不是都會先找旅日網紅的推薦清單?

這次,我們邀請擁有日本豐富旅遊經驗的🇹🇭泰國、🇨🇳中國、🇹🇼台灣網紅,帶你走進夜晚的橫濱!從玩樂路線到拍照技巧,教你怎麼拍出最美的夜景照。那些熟悉的景點,換個視角說不定會有新發現~快跟他們一起出發吧!

#japankuru #橫濱紅磚倉庫 #汽車道 #中華街 #yokohama #japankuru #橫濱紅磚倉庫 #汽車道 #中華街 #yokohama #yokohamaredbrickwarehouse #yokohamachinatown

If you’re a fan of Vivienne Westwood's Japanese designs, and you’re looking forward to shopping in Harajuku this summer, we’ve got important news for you. Vivienne Westwood RED LABEL Laforet Harajuku is now closed for renovations - but the grand reopening is scheduled for July!

>> Find out more at Japankuru.com! (link in bio)

#japankuru #viviennewestwood #harajuku #omotesando #viviennewestwoodredlabel #viviennewestwoodjapan #비비안웨스트우드 #오모테산도 #하라주쿠 #日本購物 #薇薇安魏斯伍德 #日本時尚 #原宿 #表參道 #japantrip #japanshopping #pr

Ready to see TeamLab in Kyoto!? At TeamLab Biovortex Kyoto, the collective is taking their acclaimed immersive art and bringing it to Japan's ancient capital. We can't wait to see it for ourselves this autumn!

>> Find out more at Japankuru.com! (link in bio)

#japankuru #teamlab #teamlabbiovortex #kyoto #kyototrip #japantravel #artnews

Photos courtesy of teamLab, Exhibition view of teamLab Biovortex Kyoto, 2025, Kyoto ® teamLab, courtesy Pace Gallery

Japanese Makeup Shopping • A Trip to Kamakura & Enoshima With Canmake’s Cool-Toned Summer Makeup

#pr #canmake #enoshima #enoden #에노시마 #캔메이크 #japanesemakeup #japanesecosmetics

⚔️The Robot Restaurant is gone, but the Samurai Restaurant is here to take its place. Check it out, and don't forget your coupon!

🍣신주쿠의 명소 로봇 레스토랑이 사무라이 레스토랑으로 부활! 절찬 쿠폰 발급중

💃18歲以上才能入場的歌舞秀,和你想的不一樣!拿好優惠券去看看~

#tokyo #shinjuku #samurairestaurant #robotrestaurant #tokyotrip #도쿄여행 #신주쿠 #사무라이레스토랑 #이색체험 #할인이벤트 #歌舞伎町 #東京景點 #武士餐廳 #日本表演 #日本文化體驗 #japankuru #japantrip #japantravel #japanlovers #japan_of_insta

Japanese appliance & electronics shopping with our KOJIMA x BicCamera coupon!

用JAPANKURU的KOJIMA x BicCamera優惠券買這些正好❤️

코지마 x 빅 카메라 쿠폰으로 일본 가전 제품 쇼핑하기

#pr #japankuru #japanshopping #kojima #biccamera #japaneseskincare #yaman #dji #osmopocket3 #skincaredevice #日本購物 #美容儀 #相機 #雅萌 #日本家電 #일본여행 #면세 #여행꿀팁 #일본쇼핑리스트 #쿠폰 #일본쇼핑 #일본브랜드 #할인 #코지마 #빅카메라 #japankurucoupon